Good to Great

What can you learn from jumping rope on a sunny afternoon with a little girl in your arms?

Frisbees flying, hot dogs grilling, laughter shared and relationships kindled. It doesn’t sound much like a typical first shift afternoon. For the Hopkinsville Police Department, a community cookout that drew more than 200 citizens near the city’s housing projects did more than fill some hungry bellies. It’s one part of a greater vision that has led the 114-person department to realize it’s mission of working in partnership with citizens to enhance the quality of life.

You won’t hear the phrase “community policing” come out of Hopkinsville Police Chief Clayton Sumner’s mouth. Unless it’s to say that’s not what his police department does. But if you take a look at his officers’ activities over the past year, you would see them playing in a basketball game against a group of school children to raise money for the local Boys and Girls club. You’d read about a football camp, led by HPD officers who played at both the NFL and college level, that began with some pizza and t-shirts and has grown into an opportunity to reach a unique group of kids learning about more than football.

Community policing in Hopkinsville is just policing. Bringing the police department and community together has become part of the agency’s daily fabric. Altogether, the Hopkinsville Police Department participated in more than 100 community events in 2015, Sumner said.

“If you want to know what community policing is, come spend a week here and we will show you,” Sumner challenged. “If the whole organization isn’t bought in, what good is it?”

Hopkinsville Police Chief Clayton Sumner has served as the agency head since he was appointed interim chief in fall 2014, and his position was made official just four months later. He has served the agency since 2002. (Photo by Jim Robertson)

Implementing department-wide participation in community events was a goal that began only last year, Sumner said. Everyone — from the cleaning staff to the chief — is involved. In the beginning, Sumner said there was a little grumbling about adding to the officers’ regular activities.

“Now everybody looks forward to it,” he said. “It has just become an everyday part of life.”

Sumner was appointed interim police chief in the fall of 2014, and officially accepted the title just four months later. He knew early on that immersing the department deeper into the community was a goal he wanted to pursue, but finding the right way to do it took some time. The process began with in-depth research into the demands on an officer’s time during any given shift.

“How long does it take to take a burglary report?” Sumner asked. “What about writing a ticket? Legal advice? We need to know what our officers are doing, how long they spend on a call, how long on breaks, how long on self-initiated activity. We spent months breaking down calls to come up with the time frames, and then asked, ‘How long do we want them to be involved in the community out of their day?’”

The agency already had many typical community activities, such as a citizens’ police academy and coffee with a cop. But typical activities tend to attract a typical crowd — a group of citizens Sumner felt were not the ones who always needed to hear the message the police department needed to share.

“I started wondering, how do I break away from that?” Sumner asked. “My friends and family don’t need to be convinced that we are doing a good job. We are always trying to reach out to people we haven’t reached out to yet.

“That first cookout with a cop, I can’t get it out of my head,” Sumner continued. “I’m holding this little girl, jumping rope, praying I don’t fall. It was such a large turnout and I kept thinking, ‘This is what we have to do.’”

Policing smarter

Between tossing a football and grilling hamburgers, it may sound like HPD’s officers have little time to enforce the law. But that couldn’t be further from the truth.

When Sumner and his staff studied the amount of time spent by each officer on an average shift, carving out time for them to participate in activities meant finding smarter ways to answer calls and investigate crime. The department has done that by adopting the Focus on Four crime reduction plan, Sumner said — a policing philosophy proven in Tampa, Fla. to have reduced crime by an astonishing 64 percent over nine years.

Sumner and Deputy Chief Michael Seis heard about Focus on Four during a chief’s conference and were impressed by the common-sense policing style it promised.

“It is quite impressive,” Sumner said of the philosophy. “Seis and I talked about the possibility of how it would work in Hopkinsville and went to [then-Chief] Guy Howie and explained how we thought it could make an impact. He blessed it and allowed us to start implementing these ideas. It took some time, but over the past two years we have seen a 20 percent decrease in crime.”

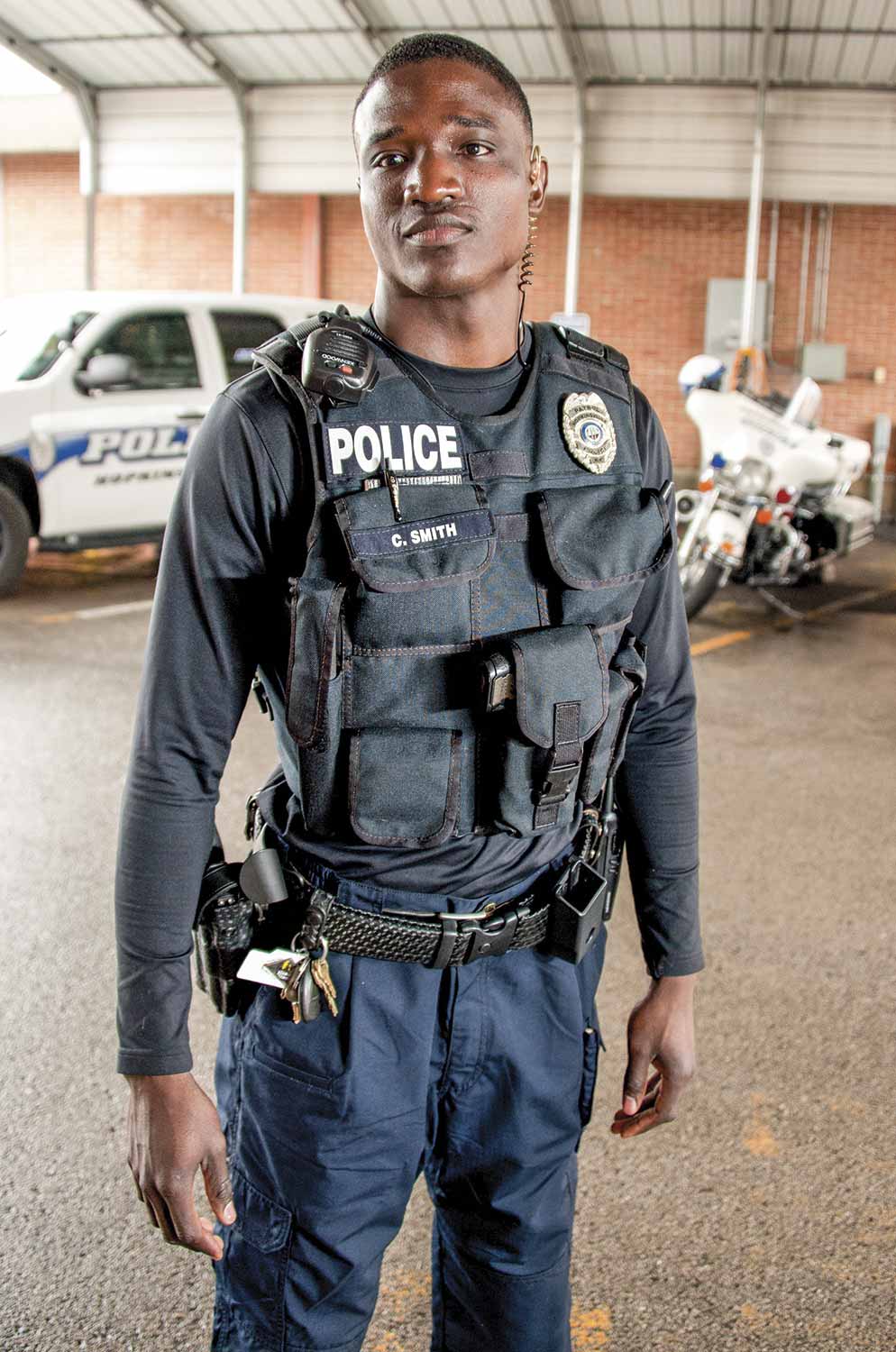

Hopkinsville Police Officer Cory Smith, one of the agency’s newest K-9 handlers, also wears an external load bearing vest. The police department sought this particular style of vest for their officers in an effort to reduce the cost associated with officer injuries and fatigue as well as to promote a healthier environment and increase officer wellbeing. (Photo by Jim Robertson)

The Focus on Four philosophy uses “four guiding components that target four high-volume pattern crimes,” according to the Tampa Police website. Those components are redistribution of tactical resources, intelligence-led policing, proactive and preventative policing initiatives and partnering with the community.

In Hopkinsville, the four crimes Sumner and Seis believed they could impact were shoplifting, theft from vehicles, burglary and robbery. Some of the strategies used to impact these crimes are as simple as using parked cruisers in high-collision areas to reduce speeding and using social media to involve citizens in catching criminals. Others are more in-depth, such as offender tracking and, of course, their developed community partnerships.

Because of the agency’s size — 78 of their 114 employees are sworn officers — Sumner said the department has developed a number of opportunities for officers to meet their goals. Non-sworn public safety officers work wrecks, take fingerprints and other minor reports that free full-time sworn officers to do other work. Three school resource officers work local middle and elementary schools while another officer serves as a mentor and runs the Gang Resistance Education and Training program for local students.

HPD is home to the local 911 dispatch center. The agency has two traffic units on motorcycles, two International Crimes Against Children officers, a full-time polygrapher, three chaplains, a SWAT team and drug strike force. The agency also employs four K-9 officers, including a bomb dog, Sumner said.

“Am I worried about drugs in schools?” Sumner asked. “Absolutely. But I am terrified of guns in schools. I’m really worried about guns on our campuses and that is one thing the bomb dog can detect, especially when we have big events.

“We have just about everything,” Sumner continued. “We are just the right size to be able to have a variety of units.”

Looking to the future

Another group Sumner said has been instrumental in returning the department’s staffing to full strength has been the recruitment team, which allowed the agency to meet many of its goals. Whether it is attending job fairs at Fort Campbell or talking to local gyms about women who may be interested in a policing career, Sumner said finding the best men and women to serve at HPD is a top priority.

“I believe we police at the will of the community. It is hard for some officers to swallow what that means. When you look at Ferguson, [Mo.], they no longer have the ability to police the community, because the community no longer accepts them.”

“Recruitment is not what it was two decades ago,” Sumner said. “How dare us sit around and expect the right person to walk in the door and ask for a job. Hell no — we need to go find them. I think it’s only going to get harder because of the retirement system. So how do we make sure we are attracting the right people?”

Part of that puzzle connects in how the police department brands itself, he said.

“Our brand has to be how we do everything,” Sumner said. “It is how our customers perceive us. In such, we have to work to build a brand that defines us before someone else does it for us. It needs to be a well-thought out process. HPD is the brand, our staff is the brand, our social media, our materials we put out — all that is our brand. As the chief, I should establish the vision and mission for the department. But it can’t stop there. I must assure every member throughout the agency clearly understands that vision as well as how their role plays into defining the HPD brand.”

Selling the brand means knowing your employees and having a good understanding of your community’s needs, Sumner said.

“I believe we police at the will of the community,” he said. “It is hard for some officers to swallow what that means. When you look at Ferguson, [Mo.], they no longer have the ability to police the community, because the community no longer accepts them. In every community there are smaller communities, and those needs often differ from one community to another. Recognizing the needs of those we serve helps to assure we truly are working in collaboration to solve community problems. It takes all of us to make this city great.”