The Truth Is Out There

American screenwriter J. Michael Straczynski once said, “Understanding is a three-edged sword: your side, their side and the truth.”

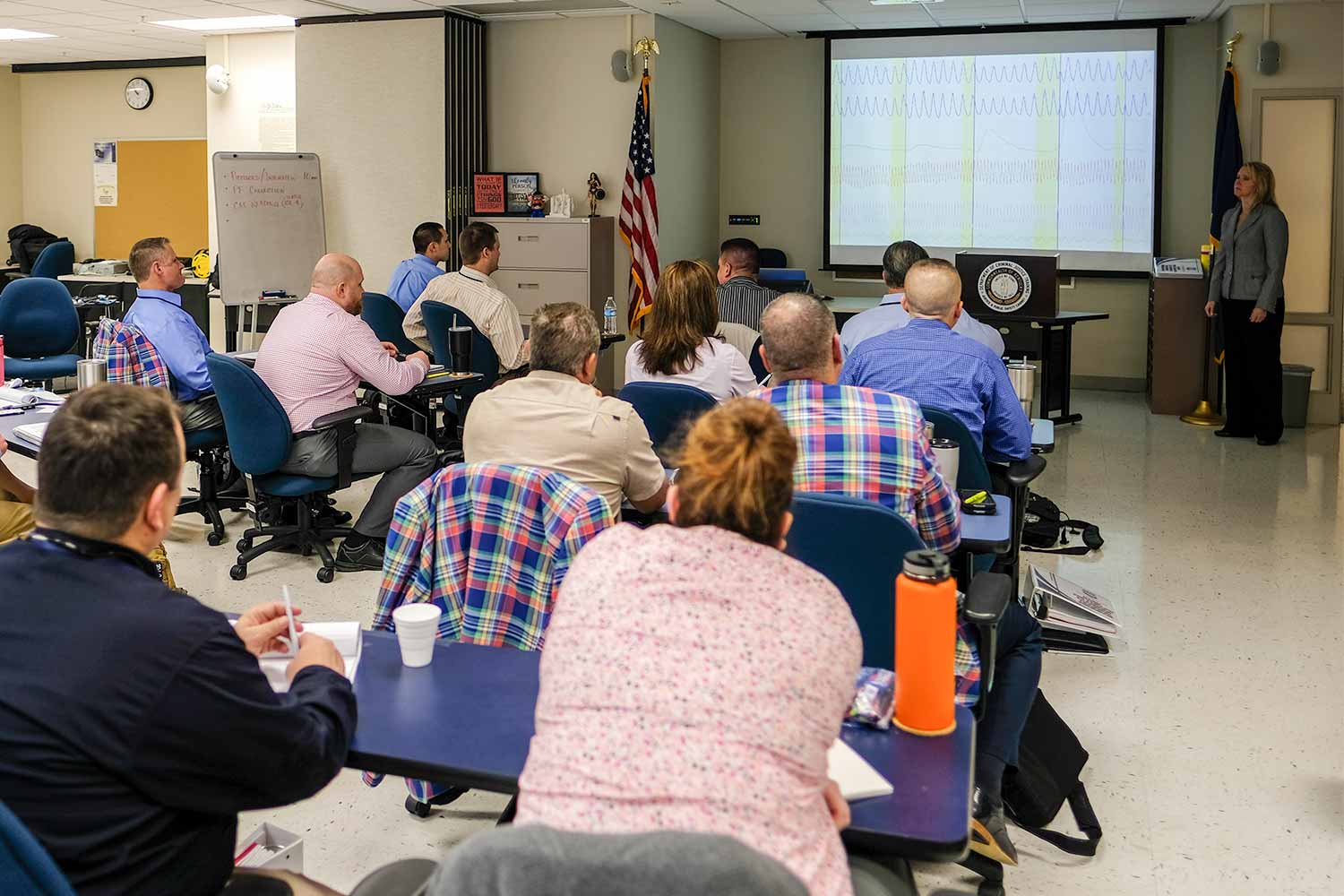

The latter is one of the reasons Kai Lynn Lim, a Singapore customs officer, traveled some 10,000 miles to Richmond in early April to study the science of getting to the truth through the National Polygraph Academy, hosted by the Kentucky Department of Criminal Justice Training.

Lim was one of 23 students – two from Singapore and 21 others from eight states – who spent 10 weeks being schooled on the art and science of polygraph.

The NPA’s course provides students “foundational knowledge necessary to administer exams, sit for state licensing exams and apply for membership in professional associations,” according to its website.

“There are so many things we have to remember. We have practicals, and you have to remember all of the test formats.”

— Kai Lynn Lim, Singapore Customs Officer and class member

Lim, who holds a degree in psychology, said prior to attending the course, she knew some basics about the science of polygraph, but the training put the entire class to the test.

“It’s tough. I don’t think there’s anyone who would tell you it is not tough,” Lim said. “There are so many things we have to remember. We have practicals, and you have to remember all of the test formats.”

Lexington police officer Elizabeth Adams agreed with Lim’s assessment.

“It’s a cumulative curriculum, so there are things that will come up from the very beginning of the course that still are very important,” Adams said. “We’re balancing coursework, classwork studies and homework assignments with practical exams, and that’s been challenging.”

Pam Shaw, NPA director of basic programs, said the program is thorough, and she has heard similar comments from law enforcement professional across the nation.

“Many of the students have said it was one of the most difficult academic classes they’ve had to take in their career,” Shaw said. “We’ve had some people say it was harder than getting their bachelor’s degree; that might be a bit of a stretch.”

Polygraph origins

According to Mike Beck, Kentucky Law Enforcement Council Polygraph program manager, the science of polygraph has been around for nearly a century.

“The first polygraph in 1921 was developed by John Larson,” Beck said. “He was the very first one to record a person’s physiology to determine whether they were lying or not with two different types of channels – blood pressure and breathing tubes.”

Since 1921, the science has become more refined and dependable, Beck said.

Present day, trained polygraph examiners monitor a person’s physiological responses when faced with threatening stimuli. Examiners use components that monitor an individual’s relative blood pressure and pulse, blood volume, respiration and upper body movement and sweat response to stimuli.

The data collected from the test is then analyzed and this will give the examiner an idea of whether a person is being truthful or deceptive.

Polygraph and policing

Law enforcement use polygraph in a variety of ways, Shaw said. Those include an array of criminal investigations such as murder, arson, burglary, assaults and sex crimes. Many law enforcement agencies also use polygraph in pre-employment screening and internal-affairs cases.

While most agencies would prefer to have an in-house polygraph examiner, Shaw said many have turned to outsourcing the service for many reasons, including budgetary.

“Some agencies find it more practical to use contract examiners,” Shaw said. “Some of the smaller departments also will reach out to nearby larger agencies with trained polygraph examiners and ask for assistance. The Kentucky State Police offers statewide assistance and Lexington and Louisville often assist other local agencies as requested.”

Course overview

The 10-week course ran from April 3 to June 9. This was the first time since 2014 DOCJT hosted an NPA course.

Students had to complete a minimum of 400 hours of training based on requirements from the American Polygraph Association, which NPA is a member.

According to the APA, polygraph examinations consist of three phases:

- A pretest interview

- Test data collection

- Test data analysis

Each phase, according to APA’s website, has an important effect on test accuracy and usefulness of test results.

During the 10-week course, students studied:

- Polygraph history

- Terminology

- Instruments used in testing

- Psychology

- Physiology

- Polygraph operations

- Test question construction

- Interview skills

- Polygraph techniques

- Test-data analysis/chart evaluations

- The validity and reliability of polygraphs

- Ethics

- Quality control

- Countermeasures (the ways people try to beat the test)

- Report writing

- Preparing for court testimony

- State polygraph laws and administrative regulations

Each week, students were tested and had to earn a minimum of 75 percent on a 100-question test in order to pass. Additionally, there was a comprehensive final exam where students must score a 75 or better.

Once students complete the course, there is still much work to do, depending on what state they are from.

“In some states, students have to go back and complete and internship program and pass a licensing exam and Kentucky is one of those states,” Shaw said.

The internship lasts one year. Currently, Kentucky has 48 licensed polygraph examiners, she added.

Following the initial 10-week class, DOCJT is hosting NPA’s one-week course on Post-Conviction Sex Offender Testing June 12 to June 16.

“It’s a bit unique in that it addresses polygraph testing for somebody that already has been convicted of a crime, and now they have stipulations by the courts and judges as to their conditions of probation,” Shaw said. “We treat it a little differently, but it’s usually fitting for law enforcement because, in polygraph, about 80 percent of conducted tests are sex-offense related.”