Resource Management

How Kentucky Law Enforcement Use Asset Forfeiture to Aid in Drug Fight

Drug investigators spend months – sometimes years – investigating traffickers whose drugs are destroying lives in Kentucky communities. Surveillance, undercover buys, confidential informants, late nights and specialized equipment demand time and money for investigations to be successful.

However, it’s all for naught if those convicted are able to pick up right where they left off with their profitable business endeavors following a short stint of time served.

That’s where asset forfeiture comes in.

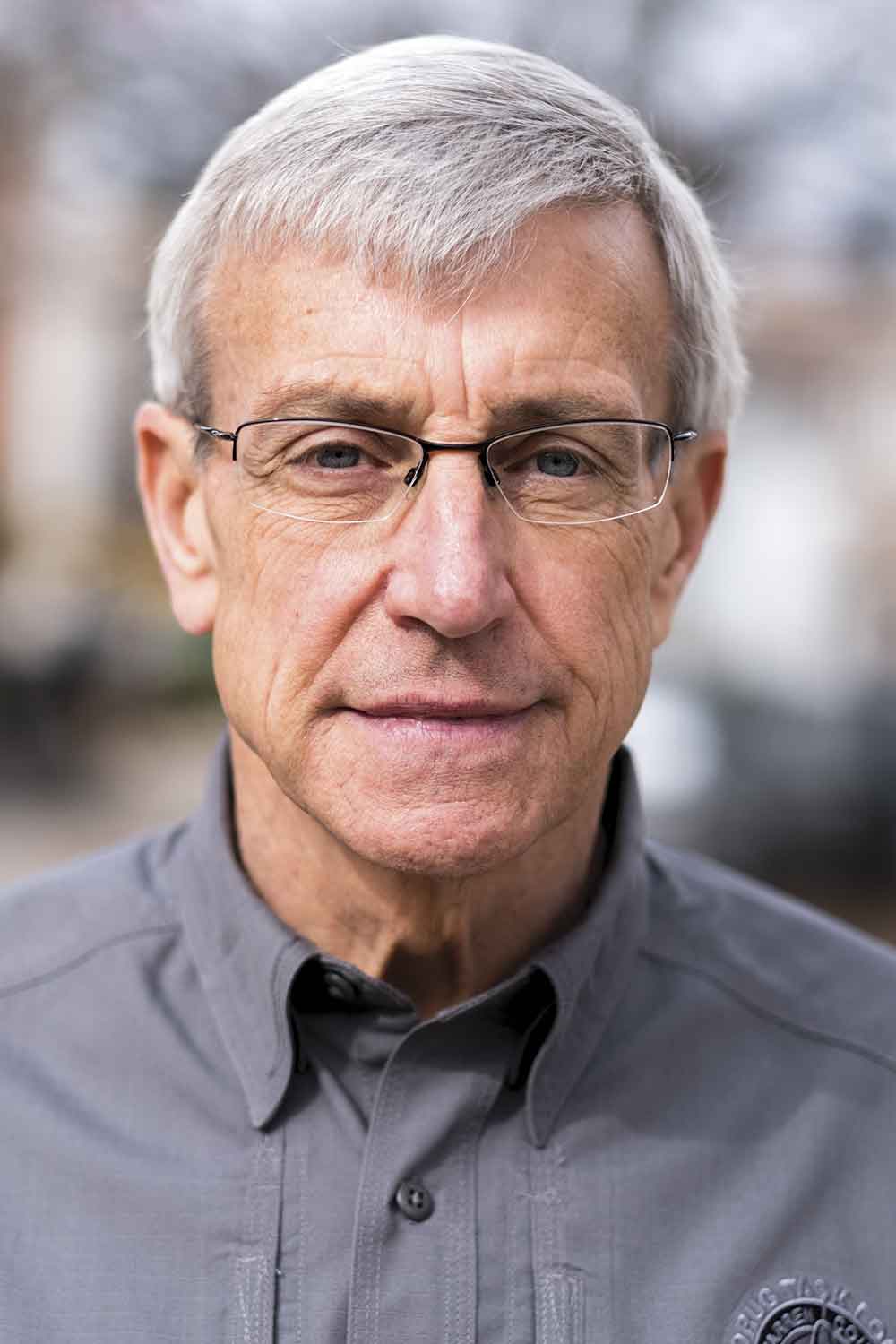

“Asset forfeiture takes away the ill-gotten gains of drug traffickers, which serves as a secondary consequence to their illegal activities,” said Tommy Loving, director of the Warren County Drug Task Force. Loving has spent more than 20 years in the role. “Since House Bill 463, many drug traffickers receive a lot less time in prison than they once did.”

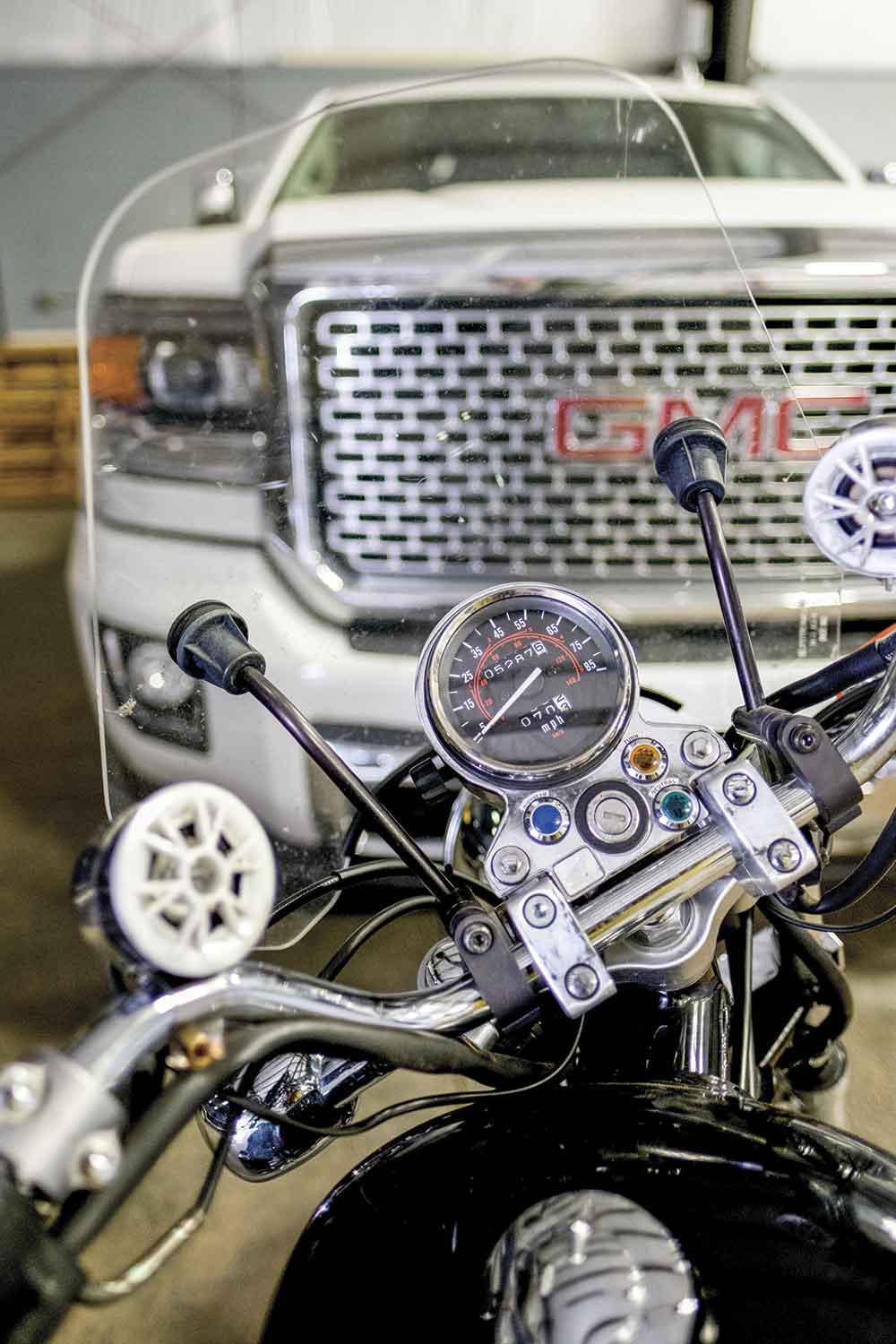

Vehicles used in the furtherance of drug activity are one type of property law enforcement should seize when utilizing asset forfeiture in an investigation. Other types of property that can be seized include homes, boats, airplanes and land that can be linked to drug sales or were purchased with profits from those sales. (Photo by Jim Robertson)

KRS 218A provides details of Kentucky’s laws regarding seizure of criminal assets. What can be seized, how it must be disposed and proper reporting procedures all are outlined. Some asset-forfeiture opponents have argued that the practice could be considered policing for profit, but Loving and Warren County Commonwealth’s Attorney Chris Cohron said the commonwealth’s laws are strong and effective.

One of the most significant components of the law is that Kentucky requires a criminal conviction for a person’s assets to be forfeited, Cohron said. The burden of proving the assets are drug-activity proceeds falls to the commonwealth.

“And there is a judicial review on top of that,” Cohron said. “Unlike a lot of complaints about federal and other states’ asset forfeiture, Kentucky law is strictly written. Before any forfeiture can be finalized, it has to be subject to judicial oversight. Just as in the policing of drug cases, asset forfeiture is never a factor in how cases are resolved. Asset forfeiture simply is a residual benefit of prosecuting drug-trafficking cases.”

Fifteen percent of forfeiture proceeds are returned to the prosecutor who adjudicated the case. The remaining 85 percent returns to the law enforcement agency or agencies which investigated the crime. Those funds explicitly are designated for training, equipment and other needs specific to those offices.

“Over the past 10 years or so, law enforcement as well as prosecutors have faced unprecedented budget cuts,” Cohron said. “We have been able to use asset forfeiture as a means to make sure we are able to effectively investigate and prosecute drug cases.”

Warren County Drug Task Force Director Tommy Loving has devoted much of his career to the fight against drug activity in his community. Loving also serves as executive director of the Kentucky Narcotics Officers’ Association. (Photo by Jim Robertson)

In the past when the legislature imposed unpaid furloughs on state employees, Cohron said many jurisdictions used asset-forfeiture funds to buy out the furloughs and kept prosecutors working. Loving, who also is the Kentucky Narcotics Officers’ Association executive director, said much of the funds his task force generates through forfeiture are used to buy drugs in investigations, purchase equipment needed to conduct cases, and could be used for overtime, if necessary.

“Drug investigations usually are complex and, many times, don’t end at 40 hours per week,” Loving said. “It also saves the taxpayers a great deal of money in having to fund drug-enforcement activities. These drug dealers, many of them are making huge amounts of cash. You can be assured they are paying no taxes. So when this money is used for a government purpose, at least that helps offset some of the missed tax revenue these people have no intention of paying.”

The scale of the problem

Narcan, overdose and heroin all are words which have become a part of daily discussion in Kentucky, as law enforcement agencies and emergency responders battle the widespread and increasing scourge of addiction. It’s a problem law enforcement faces daily, and asset forfeiture is just one tool in that fight.

According to the 2015 Overdose Fatality Report, compiled by the Kentucky Office of Drug Control Policy, overdose fatalities increased by more than 16 percent from 2014. The 2016 report is not yet available, but reports of overdoses statewide indicate those numbers likely will climb again.

“Overdose death of Kentucky residents, regardless of where the death occurred, and non-residents who died in Kentucky, numbered 1,248 as tabulated in May 2015,” the Overdose Fatality Report states. “Autopsies and toxicology reports from coroners show overdose death attributed to the use of heroin were involved in approximately 28 percent of deaths in 2015.”

Fentanyl, either combined with heroin or alone, was responsible for 34 percent of all 2015 overdose deaths, the report states.

As citizens die each day with needles in their arms, law enforcement and prosecutors need every tool available to fight against ongoing drug activity and minimize the amount of drugs available, Loving said.

“Our primary goal is to take the trafficker and the drugs off the street,” he said. “When you take their resources away, obviously that leaves less resources for them to go immediately back in business and replenish the stock of whatever drug they are selling. In that sense, it is a business – once they sell it and make a profit, they still have to restock.”

Kentucky State Police Major Jeremy Slinker, commander of the Special Enforcement Troop, and KSP Col. Steve Long, director of KSP’s Operations Division, agreed that asset forfeiture is a critical tool in continuing drug-investigation operations. In tight budgetary times, Slinker said forfeiture funds allow the agency to maintain the necessary level of investigations to attack, command and control the drug problem.

“First, I would say the thing we primarily use forfeiture funds for is to operate our drug-enforcement branches and investigations,” Slinker said. “The bulk of our money will go into evidence purchases and information purchases. Typically, the general fund doesn’t have that line item, and if it does, it’s very small. [Not having forfeiture funds] would limit how much good we can do as far as investigations go.”

Like Loving, Long agreed the asset-forfeiture program allows KSP to disrupt the flow of drugs into the commonwealth’s communities.

“Our drug guys, their main goal is to shut down operations and kill the supply, making the drugs more difficult to obtain,” Long said. “If you get enough of [the drug-sale proceeds], you can completely shut down one of those organizations.”

“Seizing drugs is a priority,” Slinker said. “Seizing money – I think the trick is it has to be proceeds from drug trafficking. You don’t just seize people’s money because they have money. You’re required to articulate how it is associated to drug-trafficking proceeds. The myths that we take people’s inheritances simply are not true. The investigation has to support the fact that it is drug proceeds.”

Meeting the need

When property is seized from a suspected drug trafficker, proper records must be maintained and submitted to the Kentucky Justice and Public Safety Cabinet, via the Office of Drug Control Policy. The records also must be submitted to the Kentucky Auditor of Public Accounts, according to Kentucky statute. (Photo by Jim Robertson)

When Kentucky State Police leaders first decided to add Tasers to the agency’s weapons arsenal, funding the equipment, batteries and cartridges was cost prohibitive for the second-largest law enforcement agency in the state.

“We had a pretty substantial seizure from a case of a chicken-fighting ring with gambling and drug dealing all intertwined,” Slinker said. “That money was forfeited to the state police at the beginning of the Taser program, and used to fund several hundred Tasers to be given out to troopers in the field or operations.”

The agency soon will upgrade its Tasers using forfeiture funds, too, Slinker said.

“A lot of times, if all we have is the general budget, we may not be able to afford some level of equipment, body armor and things like that we need,” he said.

KRS 18A.420 details how forfeiture funds can be spent. Specifically, the law states that the money is intended to supplement funds otherwise appropriated to the agency or prosecutor, and cannot supplant other funding. In other words, if an agency budgets $100,000 for the purchase of new cruisers, forfeiture funds cannot be used instead of the previously-allotted money for that budgeted expense.

“We roll our money back into accounts to continuously fund our future drug investigations,” Slinker said. “It’s not pre-determined where that money will go. But that’s probably the bulk of where our money comes from. We identify equipment needs, most of the time related to drug investigations and/or operations, and make those purchases out of those accounts.”

Proper reporting

To ensure agencies are properly using funds, the statute also outlines procedures for reporting all money and property seized. KRS 218A.440 requires that all agencies participating in asset forfeiture file a statement with the Kentucky Auditor of Public Accounts and the secretary of the Justice and Public Safety Cabinet, outlining all the money and property seized during the fiscal year and how it was disposed.

Kentucky’s ODCP Executive Director Van Ingram said the reporting forms are available online at https://secure.kentucky.gov/formservices/ODCP/AAF.

“As law enforcement officials, it is incumbent upon us to set the example by following the law and completing our requirements to report seized items annually,” Ingram said. “Law enforcement agencies can go to our website and report electronically there, or they can download the form, print it, fill it in and fax it to us.”

The reporting period runs on a fiscal year from July 1 to June 30, Ingram said. Anyone needing assistance with filing the report can contact ODCP. Following the reporting procedures keeps critics at bay and allows the state’s law enforcement to operate under the appropriate transparency.

“Despite the negative publicity we have seen from other jurisdictions, this is something Kentucky has done very well,” Cohron said. “I would encourage any agency that is not familiar with asset forfeiture, or doesn’t use it on an ongoing basis, to reach out to those agencies that deal with it on almost a daily basis. Documentation, proper accounting and putting those safeguards in place help everybody ensure this law will remain an effective tool in the war on drugs.”

Loving echoed Cohron’s sentiments.

“I also would encourage jurisdictions not using asset forfeiture regularly to go to their commonwealth and/or county attorneys and discuss the guidelines of what they are willing to do,” Loving said. “Because it is of benefit to the police agency and the commonwealth or county attorneys.”